An ancient movement technique is merging with cutting-edge technology in a novel study at The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio (UT Health San Antonio) aimed at preventing falls in people with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias.

Wei Liu, PhD, research director of the Human Performance and Rehabilitation Research Lab and associate professor in the Department of Physical Therapy at UT Health San Antonio’s School of Health Professions, said that while most research focuses on the cognitive effects of dementia, people with dementia are also up to three times more likely to experience a fall than those without the condition, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In Texas alone, falls among older adults cost the health care system $2.4 billion each year.

Liu has dedicated years to studying tai chi as a nonpharmacological intervention and exploring its potential to reduce chronic pain and prevent falls in older adults.

What is tai chi?

The exact origin of tai chi is unknown, but it is believed to stem from Chinese martial arts techniques that have been practiced since at least the 17th century. Over time, it evolved into a health practice with a series of simple but effective movements that can take years of practice to master.

“They took the movements of martial arts and developed very slow motions, using some movements that mimic the motion of animals,” Liu said.

In a squatted position, practitioners travel forward and back through 24 forms. The arms and torso perform long, fluid motions while the hips and legs execute weight-shifting movements and controlled postural changes. An expert practitioner, Liu said, can complete all the forms in about eight minutes, which they may repeat three times for a full workout or break up into shorter routines throughout the day.

In as little as eight minutes a day, tai chi’s calculated motions paired with strong muscle contraction create a significant physiological response. Potential benefits include improved balance and coordination, stability, muscle and bone strength and cognitive function.

Pepper Center award for novel study

An award from the San Antonio Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center funded Liu’s pilot study to develop a personalized mobile application powered by artificial intelligence that can “prescribe” the best tai chi exercises for individuals with early cognitive decline. Co-investigator for the study is Lixin Song, PhD, RN, FAAN, professor and vice dean of research and scholarship with the School of Nursing.

Liu said different forms are beneficial for different health conditions and the application will be able to predict the best tai chi plan for an individual’s needs. This technology could allow primary care providers to easily create a personalized plan of tai chi exercises based on health history, dementia progression and physical abilities.

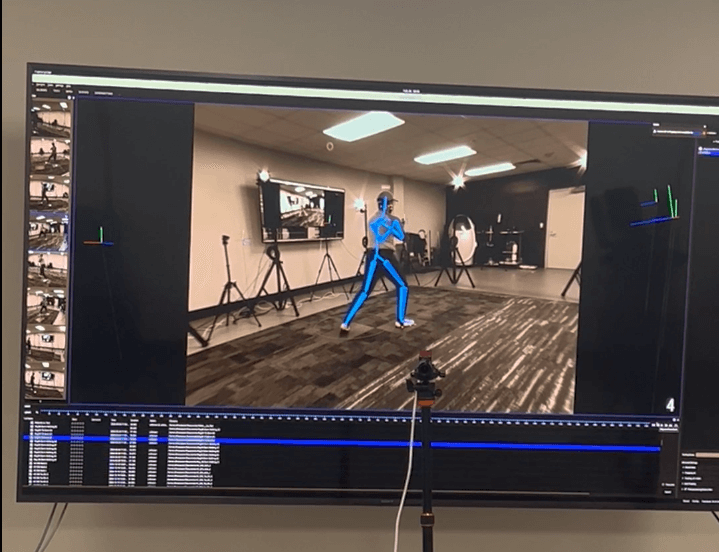

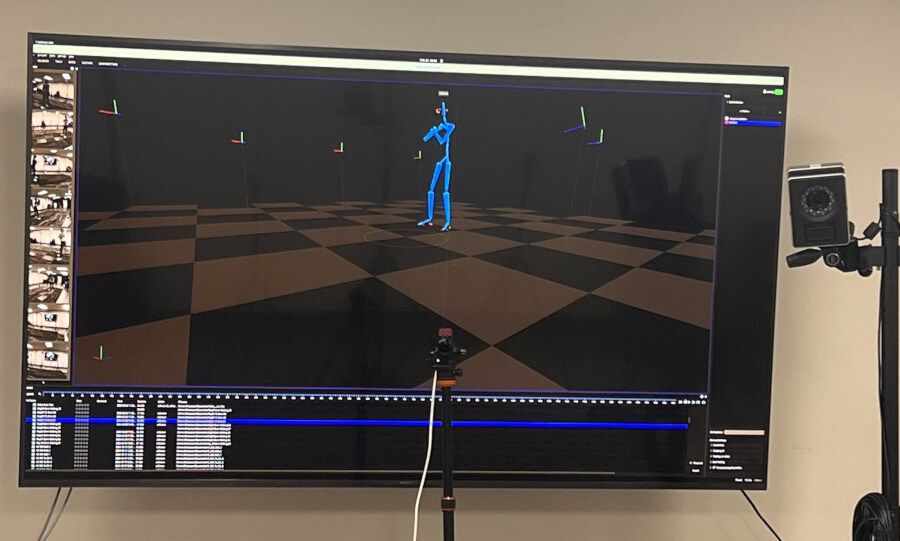

Liu’s background is in biomechanics and biomedical engineering and his previous studies observed the mechanistic workings at play when a person performs tai chi. Previous studies by Liu delved into the biomechanical mechanisms of joint load and gait involved in tai chi and how optimal forms can be used to help knee osteoarthritis pain. In his lab, dozens of motion-tracking cameras and other equipment record human movements to create a three-dimensional kinematic model and a complete individual analysis of each tai chi form.

With this current line of research, Liu is gathering quantitative proof that the practice is a beneficial intervention strategy for falls. The novel tracking system will be tested against standard marker-based technology and a small-scale trial will evaluate the success of the AI-based tai chi program in reducing falls in older people with early cognitive decline.

The goal, Liu said, is an optimized tai chi intervention that offers a streamlined, accessible option for individuals with cognitive decline who may be at risk for falls.

“We’re shaping up the strategy to be more efficient and easier to learn. Not every form has a benefit for every individual so we can pick what is best for each individual,” Liu said.

Prescription for fall prevention

Optimized tai chi could offer comparable clinical outcomes using a curated handful of forms rather than practicing all 24. For fall prevention in dementia patients, for example, Liu said researchers choose forms that increase dynamic balance.

“When you’re doing tai chi, it’s a challenge to your dynamic balance. That means you’re using your brain, connecting your muscles, then making the whole thing work. The hypothesis is that if they [people with dementia] learn how to challenge the balance, then they begin to get used to that challenging environment when they translate this motion and motor-learning skills into daily activities, like walking, and hopefully have less fall risk,” said Liu.

Liu said the research team is investigating optimized tai chi strategies for interventions in a variety of patient populations.

AI and mobile app development

In addition to the mobile application, Liu and his team are developing an AI-based platform that can evaluate patient health information to predict if tai chi is beneficial for their condition and which forms to use. Future capabilities could include integration with electronic medical records for real-time clinical monitoring, on-demand tai chi exercises through the mobile application and self-report patient evaluations.

With rising health care costs, low-cost preventive strategies like optimized tai chi could mean savings for both individuals and the health care system. Liu said non-pharmacological alternatives may help primary care physicians prescribe less medication and reduce preventable mobility complications related to dementia and other disorders.

“Tai chi is just one example. There are many non-pharmacological approaches being considered right now, like yoga and acupuncture. They are cheap and sometimes free, so if you can achieve something with a similar benefit with less cost, I think that’s what many people want,” Liu said.

Related links:

PT professor’s research featured in New York Times series on chronic pain